“Strange what being slowed down could do to a person.”

—Nicholas Sparks

Even though the gymnasium was filled with whistles, shouting, and squeaking sneakers, I can still hear the coach’s wisdom nearly forty years later.

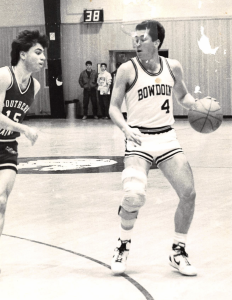

I was at SWISH basketball camp at the University of Southern Maine, a junior in high school preparing for my senior year, and college competition beyond. We were working on dribble moves—penetration with the basketball into gaps designed to draw excess defenders and create open teammates.

“Slow down to speed up,” the coach had just instructed me.

I had hurried through a hesitation crossover dribble, thinking that faster was better.

“The hesitation is of no value unless you give it the gift of time,” the coach continued. “You’ve got to give the defender time to pause in response to your own pause. You’ve got to slow down to speed up.”

* * *

Decades later, I value those same words as both a CEO and a human.

From 1997 to 2010 I was the fast-moving CEO of Hancock Lumber Company. At that time I had a booming, infallible young voice and near-boundless energy. I would routinely work from six a.m. to six p.m., racing from location to location, using first my Dictaphone and later my cell phone between stops at stores, mills, and construction sites. If there was meeting to be had, I would attend it. It there was a problem to solve, I would solve it. If there was a sale to close, I would close it.

That defined my life as an average-performing CEO of an average-performing company.

The boss gets first dibs on all the work, I’ve become fond of saying.

Then, in 2010, I had a front-row seat to a double train wreck. First, the housing and mortgage markets collapsed and average-performing companies suddenly became vulnerable. Second, in response to the stress of the first event, I acquired a rare voice disorder that made speaking extremely difficult. Without warning, or training in how to do so, I had no choice but to slow down.

It took me about five years of therapy before I could even use the phone again. Running every meeting was now impossible. I began asking questions in response to questions, to put the conversation back in the hands of the other person and protect my broken voice. Listening, delegating, sharing the stage, and doing less, not more, became my new forced modus operandi.

Only then, ironically, did I begin to learn a little something about leadership.

* * *

Today I’m a CEO who advocates slowing down organizations and the people within them.

Here’s one specific example of how I’ve pursued that path.

Over the span of several years at Hancock Lumber we were able to reduce the average hourly work week in our stores from 48 hours per week to 41. At the same time we increased annual compensation. People were making more money and acquiring the gift of time. Seven hours a week may not sound like a lot until you multiply it by the length of a career (say, thirty years). That’s 10,920 hours.

To accomplish this, we had to take on the worst possible pay structure for the twenty-first century: overtime. Overtime pay incentivizes one outcome: working longer. In the modern age of accuracy, productivity, and lean practices, what companies should reward is employees making the work take less time, not more. This can be achieved through higher hourly pay rates for everyone complemented by bonus and incentive systems that encourage themes such as accuracy, safety, and the elimination of re-work.

As human productivity at work expands, we can use some of that freed capacity to make more lumber and deliver more building materials. But, we can also use some of that newfound time to just plain work less.

Today I talk regularly about putting the work back in its place. Work should be important, not all-consuming.

My next goal is to pursue the potential of the four-day work week. For our drivers and manufacturing teams, for example, that would be four 10-hour days. If we had four delivery trucks at a store and we wanted those trucks to be on the road 50 hours a week, we would have five drivers each working four days.

Great companies will keep finding ways to help employees earn more money, but they will also increasingly give their team members something perhaps even more important: the gift of time. Work should not be hurried, hectic, or chaotic. Nor should it be all-consuming. Great companies, like great point guards, will learn to Slow down to speed up.

“Sometimes I think there are only two instructions we need to follow to develop and deepen our spiritual life: slow down and let go.”

—Oriah Mountain Dreamer

______

Thank you for considering my thoughts. In return I honor yours. Every voice matters. Nestled between our differences lies our future.